The proton as seen with a finite speed of light

Relativistic effects can be fully accounted for in producing spatial photographs of the proton by using an alternate time synchronization convention.

The Science

The structure of small particles—such as the proton—is measured by firing a probe at it, and looking at how often the probe bounces off at various angles. This gives a blurred image of the proton, due to quantum-mechanical uncertainty in the position and momentum of the proton’s center. The experimental images need to be enhanced by removing this blurring. This enhancement is typically done—in the so-called Breit frame formalism—by assuming that the proton has the same structure whether or not it is moving, an assumption that is contradicted by special relativistic effects such as length contraction and the relativity of simultaneity.

This work shows how relativistic effects can be fully accounted for in the image enhancement by using an alternate time synchronization convention. Essentially, one should consider everything they see in the direction of the proton as happening in the present. Normally—under what’s called the Einstein synchronization convention—distant events are considered to happen in the past, and a two-way signal needs to be bounced between two locations to determine the time delay and properly synchronize clocks at these locations. But these clocks are only synchronized in a single reference frame, and desynchronized in any other frame. On the other hand, if multiple clocks are set to a common time at the moment a single wave-front of light passes through them—a convention we call light front synchronization—then these clocks can still be seen as synchronized by an observer in any state of motion.

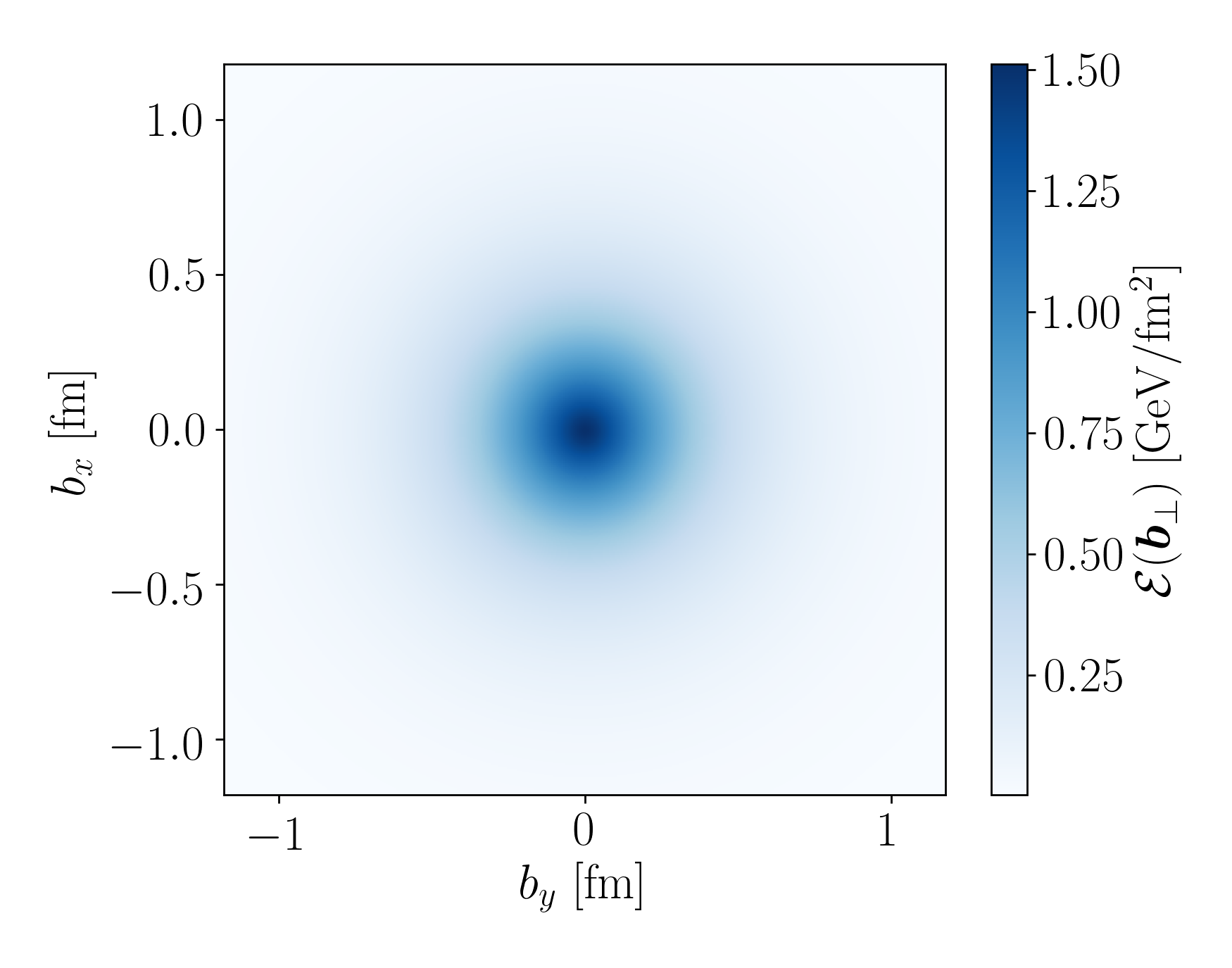

When using light front synchronization, a proton in any state of motion actually does have the same structure, allowing experimental images to be unblurred in a relativistically exact way. Moreover, these enhanced images contain optical effects arising from the finite speed of light, such as redshifts and blueshifts, and are in effect images of what the proton looks like to an observer seeing the proton using light fronts.

The Impact

Using light front synchronization, this work shows how relativistically exact distributions of energy, momentum and stresses inside the proton can be obtained from gravitational form factors—the measurement of which is a major goal of the Quark Gluon Tomography collaboration and the future Electron-Ion Collider. Several of these distributions are identical to prior results obtained in the infinite momentum frame (a formalism describing a proton moving arbitrarily close to the speed of light), though a few results are new. Most significantly, though, since proton structure is independent of the proton’s motion under light front synchronization, the results found in this work describe the densities of energy and momentum in a proton at rest.

Summary

Blurry experimental photographs of the proton can be enhanced by removing blurriness from the proton’s quantum uncertainty in a relativistically exact way through light front synchronization. This gives images of what the proton looks like with the finite speed of light accounted for.

Contact

Adam Freese

Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility

afreese@jlab.org

Publications

- Adam Freese and Gerald A. Miller, Synchronization effects on rest frame energy and momentum densities in the proton, Phys.Rev.D 108 (2023) 9, 094026

Related Links

- Veritasium, Why No One Has Measured the Speed of Light, YouTube (Educational video on time synchronization conventions)